By Scott Hildenbrand and Matthew Forgotson, Piper Sandler

Just a couple months ago, the prevailing wisdom was that banks would enter the next downturn from a position of relative strength, manifest in strong pre-provision earnings, pristine credit quality, and an abundance of capital relative to pre-Great Recession levels. Then a black swan named COVID-19 showed up on our doorstep. We are now bracing for a deep recession.

Against this painful backdrop, we examine how banks can bolster capital ratios by selling select bonds into a strong bid and using the proceeds to remove inefficient wholesale leverage. Some institutions might return the balance sheet to its original size by relevering at a wider spread.

Let’s evaluate these options from the perspective of our friends at Bank A.

Bank A’s Fundamental Profile

Bank A has assets of $500 million and its asset-liability profile is effectively neutral. During a recent review, management identifies $25 million of wholesale leverage earning a negative spread. Management decides to evaluate two strategies: Strategy 1: sell securities and pay down debt and Strategy 2: sell securities, pay down debt, and relever the balance sheet.

Strategy 1: Remove $25 Million of Inefficient Leverage

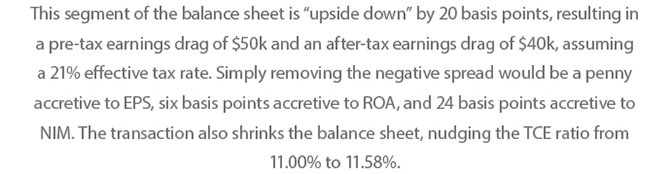

Bank A has $25 million of securities yielding 2.15% funded with wholesale borrowings costing 2.35%, as shown in the table below. This segment of the balance sheet is “upside down” by 20 basis points, resulting in a pre-tax earnings drag of $50k and an after-tax earnings drag of $40k, assuming a 21% effective tax rate. Simply removing the negative spread would be a penny accretive to EPS, six basis points accretive to ROA, and 24 basis points accretive to NIM. The transaction also shrinks the balance sheet, nudging the TCE ratio from 11.00% to 11.58%.

Simultaneously, management completes a granular review of the loan portfolio, securities portfolio, loan loss reserve, and other real estate owned. Management anticipates that a weakening economy will result in stubbornly high credit costs. Still, management determines that even in the most draconian economic scenario, the bank would remain solidly profitable. Thus, management is open to utilizing the 58 basis points improvement in the TCE ratio.

Before pressing on, three notes to consider:

- For illustrative purposes, we assume that the gain on the sale of securities offsets the debt extinguishment charge. This is convenient, but not always the case. Importantly, the relative size of these accruals dictates the impact on GAAP and regulatory capital. The realized gains on the sale of securities are accretive to regulatory capital, but most likely neutral to GAAP capital because most of the gain already lives in OCI.

Alternatively, the debt extinguishment charge reduces both regulatory capital and GAAP capital. Today, banks can sell agency MBS and agency CMBS (DUS and GNPLs) into the Federal Reserve’s strong bid to source gains that offset the debt extinguishment charge.

For what it’s worth, institutional investors tend to strip both accruals out of core earnings.

- It is self-evident that wholesale leverage earning a negative spread is inefficient. Wholesale leverage earning a positive spread can also be inefficient if it steers the asset-liability profile away from neutral in a meaningful way, clouds earnings or relative profitability metrics, weighs disproportionately on capital metrics, or precludes alternative uses of capital that could create franchise value or foment incremental demand for the shares.

- We assume removal of match funded wholesale leverage. Thus, there is no impact on the bank’s asset-liability profile. Again, convenient, but not always the case.

Strategy 2: Remove $25 Million of Inefficient Leverage and Relever at a Wider Spread

Management might choose to leverage the 58 basis points of capital by adding $25 million of match funded wholesale leverage. The net effect is to return the balance sheet to its initial size.

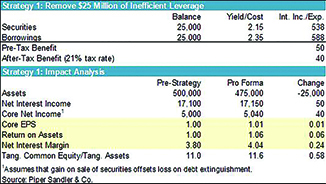

Specifically, management evaluates rolling a 3-month FHLB advance and creating term rate protection with a 5-year pay-fixed swap costing 0.55% (a.k.a. the “Beat-the-Spread” funding strategy) and deploying the funds into securities yielding 1.50%.

By executing this strategy, Bank A converts a negative spread of 20 basis points into a positive spread of 95 basis points without skewing its asset-liability profile. The strategy produces five cents of EPS accretion, five basis points of ROA accretion and six basis points of NIM accretion.

The Final Decision

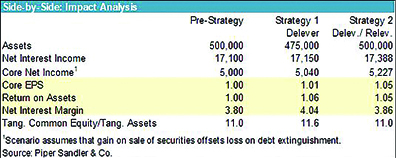

Once the strategies are built, evaluate them side-by-side.

Strategy 1 (Delever) delivers slight core net income and EPS accretion, but powerful lift in relative profitability metrics. Strategy 2 (Delever/Relever) generates more core net income and EPS accretion, but less improvement in relative profitability metrics. Critically, Strategy 1 is capital accretive, while Strategy 2 is capital neutral. Based exclusively on the numbers, management would prefer to execute Strategy 2. However, management understands that in these uncertain times, capital is king. For this reason, management executes Strategy 1.

Additional Considerations

We have structured this case study to focus on two narrowly tailored strategies, but there is so much more that banks can do right now. Three strategies come to mind straight away:

- Banks can sell MBS or CMBS into the Federal Reserve’s strong bid. Again, realized gains bolster regulatory capital, though they’re most likely neutral to GAAP capital. Realized gains can also be used to anchor a portfolio repositioning to curtail credit risk, premium risk, and reinvestment risk (i.e., fast paying bonds).

- Institutions that are participating in the Paycheck Protection Program might view the net income from the program as a “backdoor” capital raise. Banks that are comfortable with their credit and capital profiles might choose to leverage the proceeds.

- Depositories that are bracing for a deceleration in loan demand could pre-invest projected principal cash flows expected, say, over the next year. This strategy would require sourcing short-term wholesale funding, which would put temporary downward pressure on capital ratios. Still, the principal cash flows would be used to pay down the short-term debt, ultimately returning the balance sheet to its original size.

Concluding Thoughts

The key is to think holistically about your options, assessing each strategy’s impact on your institution’s asset-liability, earnings, credit, convexity, capital and liquidity profiles. Make sure that the strategy resonates in a world in which safety and soundness matter so much more than profitability and growth. If so, move forward. If not, revisit your options.

Scott Hildenbrand is a Managing Director and Head of Balance Sheet Analysis and Strategy in the Financial Services Group at Piper Sandler. Hildenbrand heads the Balance Sheet Analysis and Strategy Group, working with financial institutions on balance sheet strategy development, which includes interest rate risk management, investment portfolio strategy, retail and wholesale funding management, capital planning, budgeting, and stress testing. Mr. Hildenbrand can be contacted at Scott.Hildenbrand@psc.com.

Matthew Forgotson was the Director of Balance Sheet Analysis and Strategy in the Financial Services Group at Piper Sandler. Previously, Forgotson served as a Director in Sandler O’Neill’s Balance Sheet Analysis and Strategy Group since 2018. Prior thereto, Forgotson served as Senior Analyst and Director in Sandler O’Neill’s Equity Research Department covering small and mid-cap banks and thrifts across the United States since 2010.

This story appears in Issue 3 2020 of the West Virginia Banker Magazine.